“When I was doing science fair, I had several sleepless nights approaching deadlines,” Gayashan Tennakoon laughs as he recalls his Grade 12 year at CWSF. “I hadn’t even printed my poster yet. It was 4 a.m. the night before my flight when I finally sent it to Staples. My dad drove to pick it up while I took an Uber to the airport. He literally threw the poster at me as I was entering security.”

A decade later, Gayashan is back at CWSF in Fredericton. But this time, he’s the one reviewing posters and asking questions. As a second-year medical student at the University of Toronto, he’s returned to the fair that shaped his path as a volunteer judge. And he’s brought that hard-won perspective about what students pour into their projects.

From Anthills to CWSF

Gayashan’s curiosity showed up early. “I was born in Sri Lanka. My favourite pastime was finding anthills and putting sugar cubes next to them. I could spend hours just watching the ants work together to carry tiny grains of sugar back and forth. I loved taking things apart and just wanted to understand how the world around me worked.”

That same curiosity led him to compete at CWSF three times, in Grades 8, 9, and 12. His first experience at the 2011 Toronto fair left him awestruck. “I was new to Canada, and I’d never seen a hall that big. I didn’t even know they could make halls that big,” he recalls. “That was my first experience, even just being in that kind of environment, being with other like-minded people. I made phenomenal friends that year. People I kept in touch with all through high school.”

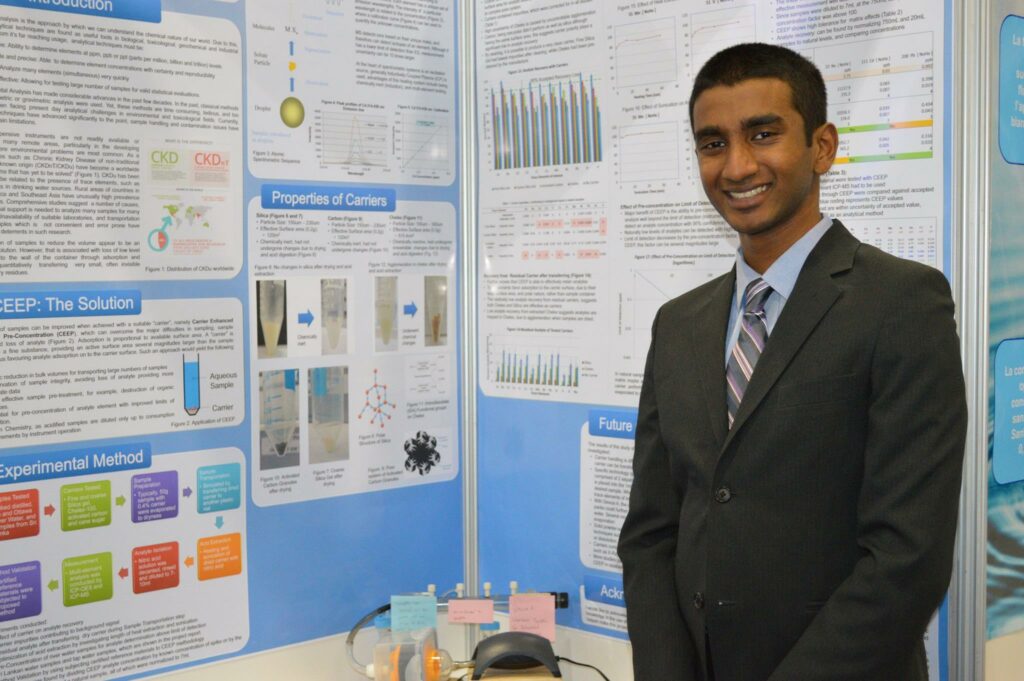

Gayashan standing in front of his project at CWSF 2015 in Fredericton.

The impact went beyond friendships. “Knowing that my work as somebody so young had merit to the scientific community, that was empowering.” That confidence and successes from CWSF opened doors to the Undergraduate Research Scholarship at the University of Ottawa, research projects, and ultimately a path toward medicine with research at its centre.

What Changed in a Decade

Standing on the CWSF floor in 2025, Gayashan sees how much has evolved since his finalist days. “The overall level of quality and competitiveness has gotten so much higher than when I used to compete,” he observes. Projects now incorporate AI and machine learning in ways that were considered cutting-edge in research just a few years ago. “When I was competing, machine learning was just starting to become accessible. Now I’m seeing students at CWSF using LLMs and doing things that were unheard of at the science fair level before.”

But what excites him most is the democratization of research. “Because there’s more accessibility to data out there, it allows kids who may not have access to labs to still carry out projects that can have phenomenal impacts. Some of these students are using open-source data and doing fascinating work that could be incredibly impactful. And they did it in their basement or in their house, on their computer.”

Seeing What He Missed as a Finalist

Returning as a judge gave Gayashan an entirely new appreciation for what makes CWSF possible. “I don’t think as a finalist I appreciated just how much work goes into putting the Canada-Wide Science Fair together,” he reflects. “There are so many kids coming from so many different places. The logistics of coordinating with all the different regions, making sure everyone’s fed, housed, and their individual needs accommodated, that’s an incredible amount of work.”

Meeting board members and planning committee members opened his eyes further. “You can just see how it’s not just a job for them. This is their life. They’re teachers, educators, professors, and they want to see these kids grow because that’s what they do for a living. This is really an extension of their own passions.”

He remembers talking to one board member who would speak of nothing but what he’s doing as a teacher and how the science fair is going. “You can really see that the people who help organize this, they really get it and they really care. I think that’s so inspiring because when you’re a finalist, all you think about is the judging. It’s easy to lose sight of everything else that’s going on. You’re in this phenomenal place for a week with such bright minds around you, and that would not have been possible without the immense amount of work these dedicated individuals put in.”

Learning as Much as You Teach

When people ask Gayashan why someone should become a judge, he starts with an honest assessment. “I will admit, for a lot of people, it can be a huge commitment of time. If you’re doing excellence award judging, that’s one full day. Special award judging can be half a day or a full day, depending. That’s something you have to work out with your employer.”

But then he gets to the reasons that make it worthwhile. “The science fair would not be possible without judges. The body of volunteer judges is what really drives what the science fair is, being able to celebrate and recognize the phenomenal projects that these students put together.”

And then there’s what judges themselves gain from the experience. Gayashan lights up as he talks about what he learned over two days of judging. “I never knew what Holstein cows were… that they are so important to Canada’s dairy milk production, and how dairy farmers can track the pedigree of the cows we have. I learned about a new way to measure the size of distant galaxies by looking at calcium absorption. I learned that we have a huge infestation of clubroot fungus affecting Saskatchewan and Alberta, which led Alberta to shut down its canola oil production. And then there’s balsam fir, which is a huge economic driver but is being devastated by root rot fungus.”

He pauses and laughs. “Basically, you learn a lot as a judge, too. I love that these students use their unique lived experiences and perspectives, which directly reflect the types of projects they’re doing.”

What Really Matters in a Project

After two full days of judging, Gayashan has clear thoughts on what makes a strong project. “Research questions can be answered through so many different approaches. I think a phenomenal project is when a student has considered multiple avenues and can answer this is why I chose to answer this research question this way. With this comes being able to understand what the limitations of their approach are.”

It’s not about having all the answers. “If they’re able to give you a sense that they’ve considered what other ways they could have gone about this and they have an answer for that, that’s phenomenal. It really shows they have a strong grasp of the work they’re doing.”

The other key element? Passion rooted in experience. “There were a couple of students who had some powerful lived experiences that you could tell they used to directly inform the type of project they’re doing and the way they actually carried out their project.”

His advice for finalists wanting to do their best project? “Have a strong foundational knowledge of what your project is and what’s happening in current research for it. Then be able to answer: why is this question important and what does it mean to you or the people around you?”

Why STEM Projects Matter Now More Than Ever

Ask Gayashan why every Canadian student should do a STEM project, and his response is topical. “I don’t want to get super political about this, but I think it’s actually really important to talk about.”

He takes a breath and continues. “What doing a project gives you is a sense of critical thinking. It’s the one avenue in your day-to-day life as a student where you’re not really told what to do. You have the opportunity to explore what you’re interested in and apply your critical thinking to that project.”

The stakes feel higher now. “If you look at day-to-day life today, we have so much misinformation going around. There’s even, for lack of a better term, a hostility towards the sciences directly stemming from some of that misinformation. I think empowering youth to think critically, to examine on their own, is the source of information I’m looking for something credible? Should I trust it? What biases does this have? Similar to how, when you yourself are doing a project, you might have certain biases and examining that can directly translate into how you’re able to critically evaluate information that’s coming to you on a day-to-day basis.”

His voice gets more emphatic. “Critically evaluating that you’re being informed by sources that are accurate, that are factual and are based in science is so crucial. At the end of the day, I think that’s important for every single person, regardless of whether you’re in the sciences or not.”

Finding Hope in 300 Solutions

Perhaps the most powerful thing Gayashan takes away from judging isn’t technical knowledge or networking; it’s not even just a sense of giving back. It’s something more.

“There’s so much negative information that gets fed to us all the time, and you feel like the world’s going to fall apart,” he says. “But then you come here, and there are 300 different projects for solutions to 300 different problems. You can’t help but feel some level of faith restored in the world around you. It’s incredible to see that these young minds are tackling the solutions to some of the world’s biggest problems.”

Over 160 volunteer judges conduct more than 2,500 judging sessions at CWSF each year.

For someone in the throes of medical school and “adult” life, judging offers something else too. “When you have a daily 9-to-5 job, you don’t really get a lot of time to be that curious kid again. You have these tasks set in front of you, your weekly deliverables, and your boss you have to report to. But when you’re here [at CWSF], and you’re talking about clubroot fungus. The next project will be about milk production. The other project will be about how we can characterize galaxies. The next project will be about how we can solve eye disease.”

He smiles. “It brings you to an environment that is nothing like what you’d be doing in your 9-to-5 job. Being able to explore that side of you that is curious and actually being a kid again in a way, too. Being able to be like, hey, this is so cool. I’d love to learn more about this.”

Full Circle in Fredericton

Standing in the same city where he competed a decade ago, Gayashan sees the experience differently now. “I remember being this antisocial recluse for the first few days until judging was over. I was so stressed about awards,” he laughs. “But looking back, what mattered most wasn’t the awards. It was that I went to this national-level competition. Even on my résumé now, people see CWSF and recognize it as a huge accomplishment.”

The numbers back him up. Roughly 500,000 students do STEM projects each year, in classrooms or at home. About 20,000 compete at regional fairs. Only 400 make it to CWSF. “That’s the top one percent. You should be proud of that fact, regardless of whatever extra awards you get.”

His perspective on judging has shifted, too. “I think it can be really easy to lose sight of how much work each project took. Because all these projects are of such a high standard, regardless of whether a project does well or not, it’s so important to celebrate the amount of work that a student put into it.”

He thinks back to his own experience as a nervous finalist. “These judges are so nice. They really want to celebrate the projects and be there for the kids. Sometimes, as a judge, I worry I come off as too strict because I ask tough questions to gauge knowledge. But it’s completely fine if a competitor can’t answer every question. The judging process can be intimidating because judges have limited time, but outside that environment, judges are just people who care about supporting young scientists.”

Why He Came Back

When the judge recruitment email appeared in his inbox, Gayashan didn’t hesitate. “You get to celebrate and potentially foster the growth of some incredibly brilliant young minds. There’s something so rewarding about being able to say, hey, you did phenomenal work. I’m here to congratulate you for that phenomenal work you’re doing. There’s a lot of self-actualization that you’re able to get out of that by celebrating these projects.”

Gayashan returning to CWSF 2025 in Fredericton, 10 years since stepped foot on the Project Zone floor as a finalist.

For Gayashan, judging has become a way to complete the circle. To be the encouraging presence for students that judges once were for him. “When you do research, especially in a wet lab, you’re holding something in your hand that probably nobody else has made before. That’s so cool,” he says, his eyes lighting up with the same curiosity he had as a kid watching ants. “And getting to celebrate that with the next generation? That’s why I came back.”

Interested in judging at CWSF? Applications open in the fall. Learn more about becoming a volunteer judge at cwsf-espc.ca/judges.